Wild and hatchery-spawned fish are commingled in this fall's Chinook salmon run on the Washougal River in southwestern Washington state. The state Dept. of Fish and Wildlife wants them separated and has turned to an engineered solution for help.

Whooshh Innovations, Bellevue, Wash., is trapping migrating salmon, manually culling marked ones from hatcheries and, from the river, shooting them live through a pneumatic tube, up a high bank and into tanker trucks. The peak so far is 400 fish a day, but the rate is expected to rise as autumn rains hit and increase the number of migrating fish.

Vince Bryan III, CEO, says the company has a two-month permit window, ending in late October. The firm is using for the first time its 120-ft-long mobile transport unit in what he hopes will be many more live-fish transfer operations.

The system was engineered to handle live fish without harm, based on lots of experiments with dead ones. Its design is adapted from a system used in fruit packing, which requires a tender touch.

Whooshh employs a tube made of a proprietary thermoplastic material and a blower that can either pull or push fish through the tube at 16 ft to 32 ft per second. The live-fish system was first used commercially with dead fish about a year ago at a processing plant in Norway. It is working well, and engineers are installing a 450-ft-long run at a second site.

"There are certainly a lot of trade secrets to what we have learned works well," Bryan says, adding, "Obviously, it makes sense to start with dead fish."

In Washington, Eric Kinne, a Dept. of Fish and Wildlife hatchery reform coordinator, says he worked with Whooshh on improvements for three years before signing off on the Washougal project.

In this first application, a weir across the river directs the commingled wild and hatchery fish into a trap, where workers separate them by hand. The wild fish are allowed to continue upstream, while the hatchery fish are diverted into the system.

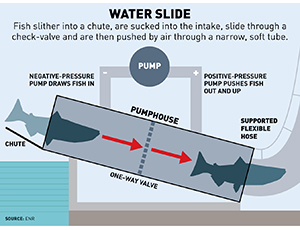

The Washougal project uses flowing water to move the fish into the tube, which is sized to fit their girth. They can be hand-fed or, attracted by the flow of water, swim voluntarily into the intake. After the vacuum pulls them in, they pass through a one-way valve and then into a second area, where pressure from behind pushes them along. The average pressure in the tube, which uses water as a lubricant, is 1 to 2 psi. Tests show no scale loss or evidence of damage to the eyes. The fish are fine out of water for the few seconds it takes to move them.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment