The only person criminally prosecuted for the deadly collapse of a 200-ft tower crane in Manhattan was acquitted last week of all charges, but New York City’s sweeping safety reforms following the accident remain in place.

New York Supreme Court Judge Roger Hayes’ tersely worded verdict declared master rigger William Rapetti not guilty on a multitude of charges, including manslaughter and negligent homicide for his role in the collapse that killed seven and injured dozens more. But several regulations imposed by the city’s Department of Buildings (DOB) in the wake of the collapse, including a ban on the use of nylon slings used to temporarily hold a crane’s collar to its mast during “jumping,” or extending, operations, still must be observed.

The slings were at the center of the case against Rapetti, who was accused of using only four slings—one of them damaged—instead of the manufacturer’s recommended eight. Some national crane experts say the DOB’s rules unnecessarily complicate the use of tower cranes, especially since Rapetti was acquitted.

“Synthetic slings should not be condemned. They’re excellent,” says Edward Shapiro, president of the Heavy Equipment Services Co., Niantic, Conn. “All of these devices are fine if they’re used within their operating parameters. They’re lighter [and] more user-friendly.”

Despite Rapetti’s acquittal—and with 58 civil suits still pending against Rapetti and his firm, Rapetti Rigging Services, Massapequa Park, N.Y.—there is plenty of blame going around as to what caused the tragic accident.

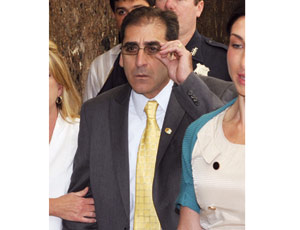

During the trial, Rapetti’s attorney, Arthur Aidala, argued that the crane collapsed because the developer of the rising condominium on East 51st Street rushed construction during the tail end of the city’s housing boom in late 2007 and early 2008.

In particular, the defense claimed the crane’s installation engineer rushed the welding of the tie-beams on the building’s ninth floor, sped up the crane’s computer- controlled joystick and used an unorthodox design that did not bolt the crane to the ground. The crane’s computer system also was revealed to have been beset with problems for months before the crane collapse.

Throughout the trial, Aidala accused New York City of “incompetence at the highest levels of city government,” noting that DOB inspector Edward Marquette was indicted for saying he inspected the doomed crane when he allegedly did not.

Domino Effect

Howard Hershenhorn, who represents the wife of victim Wayne Bleidner in one of the civil cases against Rapetti and several defendants, says a “domino effect of errors” caused the crane to tumble.

“This does not really appear to be solely [the fault of] Rapetti, but rather a combination of fault by several different people and entities that led to this calamity,” he says.

Steven Dorfman, the attorney for injured civilian John Gallego, who testified during the trial that he was “buried alive” by the fallen crane, agrees with that interpretation. “In the past, everybody was trying to point the finger at Rapetti and lay the blame on him. They can’t really do that now,” he says.

Although Hershenhorn acknowledges that the allegedly absentee inspector makes for a “sexy case against the city,” he doubts New York City will suffer much “practical fallout” because it is difficult to prove a proper inspection would have prevented the collapse.

The city has been battered since the beginning of the trial with accusations of the DOB’s incompetence as well as the unraveling of the prosecutor’s case against the man it blamed for the tragedy.

Throughout the trial, several of the prosecution’s witnesses seemed to aide Rapetti’s defense by speaking highly of the embattled rigger and contradicting the prosecutions’ allegations.

DOB spokesman Tony Sclafani pointed out that the department enacted “a number of reforms” following the collapse, including increased oversight, mandated training courses for tower-crane workers and increased inspector training as well as tracking the locations of all inspectors via GPS.

DOB announced the ban on the slings after a study by Ove Arup & Partners Consulting Engineers PC blamed them for the 2008 Manhattan collapse. The engineering firm’s finding led to Rapetti’s indictment.

In addition to changing how crane safety equipment is used, the aftermath of the 2008 crane accidents are likely to draw attention to training and certification procedures for riggers, signalers and operators. Six years after a set of guidelines were first proposed, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration is expected to soon unveil its new certification procedures.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment