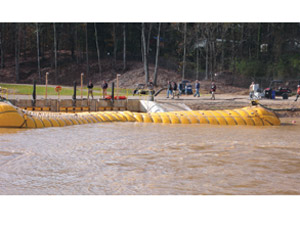

Within a few seconds in mid-December, engineers at a new research facility in Vicksburg, Miss., sealed a 2,000-cu-ft-per-second torrent of water pouring through a 40-ft-wide, eight-ft-deep levee breach using a 100-ft-long, 15-ft-dia., air- and water-filled fabric tube rolling in the stream.

The Dec. 15 event was the first full-scale demonstration of rapid levee repair technology developed by the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center in Vicksburg and the Dept. of Homeland Security’s Advanced Research Projects Agency. Now researchers hope private interests will take the technology to an operational level.

“We are confident we can seal 80-ft breaches,” says Donald Resio, ERDC’s senior research scientist.

Col. Kevin Wilson, ERDC commander, says DHS funded the $4.1-million, 11-acre, four-million-gallon levee breach model facility using five criteria. DHS required that the repair must be implemented within four to six hours, perform in austere conditions, require little site preparation, require little logistical support, and be deployable by helicopter, vessel or truck. ERDC’s tubes meet all the requirements.

Ironically, the morning of the demonstration, Resio got an urgent request for tubes to repair a two-week-old levee breach on the Dique Canal in Colombia, South America. “If we had gotten there within the first two days when it was 150 ft wide, we could have saved lives and millions of dollars in damage,” Resio says.

By Dec. 17, the Colombian breach was 210 meters wide, with water flowing 1,450 cu m per second. Up to 800 million cu m of water had inundated 400 sq kilometers, according to the Corps’ Mobile District, which provides military and construction support for Central and South America.

“Every year levee breaches are responsible for loss of life and billions of dollars in damage,” says Resio. He says the technology to quickly seal them is ready, but it still needs “a planning group that says we are the people responsible for deploying it,” Resio says.

Wilson says that about 75% of breaches are small—40 ft wide or less, particularly in the first hours. But other than the tubes, there is no technology to seal breaches other than “the old standby”—that is, sandbags. “Sandbags are slow to deploy and not very effective,” he says.

Full-Scale

The test facility has a three-tiered, gravity-fed system of basins. The source basin at the top is 94 sq ft at the base, a maximum water depth of 20 ft and a 2.2-million-gallon capacity. It feeds the test basin, which measures 120 ft wide by 150 ft long at the base, with a maximum water depth of 9.5 ft and a 1.6-million-gal capacity.

The test basin has a collapsible weir to simulate the levee breach. Water flows through the breach into the catch basin, where the capacity totals more than four million gal.

Malouf Construction, Greenwood, Miss., broke ground on the project last June and finished construction by late October. The project required moving and reshaping 60,000 cu yd of dirt, installing about 900 ft of 54-in. corrugated- metal pipe, placing concrete pads at the base of two of the basins and installing the gate structures, says Brian Atkins, project manager.

The Corps decided to use a full-scale, 100-ft-long, 15-ft-dia tube as a proof-of-concept demonstration “because it is perceived to be the most difficult,” says Resio. ERDC had successfully tested variously shaped yellow rubber tubes to model breach repairs at 1:4 scale at the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture’s Hydraulic Engineering Research Unit in Stillwater, Okla., but until now there existed no facility in the U.S. large enough to go to full-scale.

Jack Brown, vice president and production manager of tube manufacturer Kepner Plastics Fabricators Inc., Torrance, Calif., says they are made with a heavy-duty, vinyl-coated polyester base fabric that is about 1/16 in. thick and has a 1,250 lb per in. tensile strength, a 275 lb tear strength and a weight of 47 ounces per sq yd.

“When we make our primary product line—oil-spill containment booms—the material is about half as thick as this,” Brown says.

Further, the tube sports a 3-in.-overlap, welded-seam construction and is reinforced with 10 longitudinal, treated polyester webbing straps, each rated at 20,000 lb, and 22 circumferential straps, each rated at 15,000 lb. Brown says other features include a towing bridle at each end as well as 22 four-in. fill and drain connections.

Safety First

The tube also has 44 D-rings to aid handling by a small crew positioned safely away from the breach, To demonstrate,...

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment