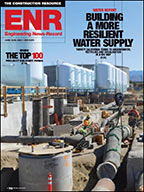

Aurora, Colo., took a big step to avoid becoming a dry city with the fall completion of Prairie Waters, a $653-million pump, pipeline and purification project.

During the drought of 2002, Aurora, a suburb at the eastern edge of Denver, saw its reservoirs plummet to 26% of capacity, a critically low level the city is unlikely to suffer again, even in future dry spells, thanks to the $1.1-billion, 10-year capital improvement project. The city water-system upgrade adds 3.3 billion gallons (10,000 acre-ft) annually to the available supply—a 20% increase.

The project uses water collected by 17 high-capacity alluvial wells drilled within 200 yards of the banks of the South Platte River in Weld County, Colo. The well water is delivered first to the North Campus aquifer-recharge-and-recovery basin, then, via 34 miles of 60-in.-dia pipeline and three pump stations, to the Peter D. Binney Purification Facility near the Aurora Reservoir.

For the final step, purified water moves from Binney to the Robertsdale Tank & Pump Station for distribution to residential customers.

“The water resource is so scarce today in the arid-American West that you can’t just go out and appropriate new water,” says Mark Pifher, director of the city’s water department. “So you have to find a way to make use of what you have. And I think what we have here is a model for similar projects in the West.”

Englewood, Colo.-based CH2M Hill designed the North Campus and managed the overall project; MWH Americas Inc., Denver, designed the pipeline, and Brown & Caldwell, Golden, Colo., designed the Robertsdale station. Different contractors laid each of the three pipeline segments. Portions of two segments parallel a 14-mile stretch of the E-470 tollway east of the metro area.

“Prairie Waters is somewhat unique in its use of multistep purification and puts Aurora center stage in the application of advanced water-treatment technology,” says Rod Brauer, CH2M Hill’s Prairie Waters program manager. “At Binney, up to 50 million gal of water, depending on demand, is passed through a succession of 13 treatment buildings.

From start to finish, the processing cycles are: softening, chemical pretreatment, UV disinfection, natural sand-and-gravel filtering and granular activated-carbon adsorption.”

The ultimate goal, Brauer says, is to ensure that water from Binney is “indistinguishable” from the mountain-sourced water stored in Aurora Reservoir. Custom manufactured in Toronto by Trojan Technologies Inc., Canada, UV oxidation units remove as-yet-unregulated pharmaceuticals and trace elements that are likely to be regulated in the future. Carbon adsorption accomplishes the “final polishing” of the water, removing pollutants that affect odor and taste.

The entire system can be monitored and operated by a single technician from the computerized control center at Binney. Data is transmitted via fiber-optic cable running parallel to the pipeline. “The high-tech control system, including numerous valves and monitoring devices, was a huge component of the project,” says Lee McIntire, president and CEO, CH2M Hill.

Budgeted for $754.8 million, Prairie Waters came in well under that total at $653 million. Construction wrapped up in April 2010, followed by a requisite six-month start-up and testing period.

“For a project of this size to be under budget and on time is a testament to those who have worked to implement it,” says Pifher. “We were the beneficiary of an unfortunate, deep recession. As a consequence, there were many contractors looking for work and bidding as low as they could to keep their people employed.”

Further, during the project, prices for steel and concrete fell, which also made the project more affordable, he says.

The facility became fully operational on Oct. 8, nearly three months ahead of the scheduled December completion. Water officials have begun testing water quality along the pipeline, which could be ready for use in January.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment