Florida state lawmakers and Congress members are racing to retain $2.4 billion in federal stimulus dollars committed to build high-speed rail, while other states await the opportunity to gain those dollars that Gov. Rick Scott (R) rejected this month.

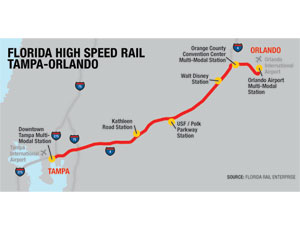

The funds represent 90% of what the Florida Dept. of Transportation says is needed to build a line from Orlando to Tampa. The governor cited concerns about potential capital cost overruns, optimistic ridership and revenue projections, and the fear that taxpayers would be burdened with repaying the money if the construction or operations were halted.

Bob Burleson, president of the Tallahassee-based Florida Transportation Builders’ Association, says the last point was crucial. “The real issue was—even if the private sector guaranteed they could build it with no additional cost to the state—if five years or eight years from now they walked away, the state could be left holding the bag to either pay back the money to the federal government or pay to operate the train for 20 or 30 years,” Burleson says.

Scott voiced support for investment in ports, freight rail and highways. But the U.S. Dept. of Transportation will not reallocate that money to other projects in Florida. “There is overwhelming demand for high-speed rail in other states that are enthusiastic to receive Florida’s funding and the economic benefits it can deliver,” said DOT Secretary Ray LaHood in a written statement.

“We worked with the governor to make sure we eliminated all financial risk for the state, instead requiring private businesses competing for the project to assume cost overruns and operating expenses,” he added.

When Republican governors in Ohio and Wisconsin turned down federal dollars for high-speed rail, the $1.195 billion went to other states, including Florida and California. Many Republicans have praised the governor, but not all. State Sen. Paula Dockery (R-Lakeland), a member of Scott’s transition team, noted in a statement that Scott did not allow the private teams interested in building, financing, operating and maintaining the train the chance to submit proposals.

U.S. Rep. John L. Mica (R-Fla.), chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, has urged Scott to reconsider. On Feb. 18, he announced a “rescue plan” for the first 21-mile section—from the Orlando airport to the convention center—with Orange and Osceola counties and the city of Orlando to receive the funds and solicit private-sector proposals. But the federal government rejected that plan. The parties involved now are trying to form a group to receive the funds and oversee the project, but the governor remains firm in his opposition to the line being built.

Several consortiums had expressed interest in designing, building, financing, operating and maintaining the line. Aside from expressing disappointment, most declined to comment. Industry experts, who generally refer to transportation as non-partisan, differ as to what extent the governor’s decision motivated by economics or politics. “While the governor’s concern for billions of dollars in construction cost overruns is likely overstated, his concern for inflated ridership numbers is not,” says Kevin Coates, executive director of the North American Maglev Transport Institute, noting the two cities’ sprawl and lack of transit connections. “Even as an advocate for maglev, a first line between Tampa and Orlando does not make sense,” he adds.

Tom Warne, a consultant and former chief of Utah’s transportation agency, says the governor’s decision echoes a general trend of financial caution, not politics. “More and more, people are examining the true cost of the federal dollar,” he says. However, he concedes there may be a bias against public transit. “There is a perception that transit should do more to pay for itself. But people forget that highways don’t make money either,” he says.

Melissa Lafsky, editor-in-chief of the website Infrastructurist.com, says Scott’s decision was “nothing short of a political move. His justifications are based on hollow reasoning. The state would not get stuck with the bill for any overages.”

Regarding general opposition to Obama’s high-speed-rail vision, Emil Frankel, director of transportation policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center, adds that general “ad hominem endorsements or attacks on high-speed rail miss the point. I am a little concerned that, even in transportation, partisanship is beginning to be a stronger factor.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment