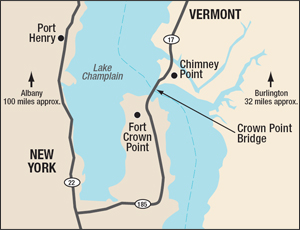

New York State Dept. of Transportation officials swiftly are preparing design concepts for a new crossing to replace the Crown Point Bridge, abruptly closed in October due to unexpectedly high levels of pier deterioration. Meanwhile, contractors are racing to build temporary vehicular ferry-terminal facilities at Lake Champlain between New York and Vermont as a stopgap measure.

NYSDOT, in conjunction with the Vermont Agency of Transportation, on Oct. 16 shut down the 80-year-old, 2,184-ft-long steel truss linking Crown Point, N.Y., and West Addison, Vt., after an emergency diving inspection confirmed what a standard biannual inspection had found—cracks in the center piers were far worse than they had been just a few years ago.

Variable channel depths, frozen bearings, bridge age and unreinforced concrete all came under suspicion. “A consultant doing biannual inspections noted the deterioration,” says Ted Zoli, technical bridge director with HNTB Corp., Kansas City, Mo., NYSDOT’s design consultant. “We took a boat ride and got close to the piers. They looked bad, worse than I had thought.”

The two 10-ft x 40-ft concrete columns sit atop caissons in the river. “They are unreinforced-concrete piers,” notes Robert Dennison, NYSDOT chief engineer. “The lake has variable depths—that is a problem that was not contemplated by the original designer.” Ice freezes first near the edges of the lake, then expands and pushes up against the center piers with greater pressure, he explains. “Lake ice usually shoves up against the shore,” says Zoli. HNTB, which already had been leading a team preparing environmental documents for a planned new bridge, now is helping plan demolition of the old bridge and hastening development of new bridge concepts to present to the public in December. “My goal would be to start demolition by the end of the year,” says Dennison. “But we are going through the permit process, solicitations...the absolute limit is that we want [the bridge] out of the water before recreational traffic returns to the lake.”

The state governors received a final report on the bridge on Nov. 9 that stated, “If any major cracks were to develop diagonally in the pier or deterioration reduces the contact bearing area between concrete segments, the pier could fail without warning. The risk and safety for personnel working in close proximity to the existing, fragile bridge is too great to permit rehabilitation in any form. Moving forward, the existing bridge should be razed in a controlled manner, eliminating the risk of sudden, potentially catastrophic, bridge failure.”

The 3,500 daily users of the bridge have no alternative for 100 miles. Kubricki Construction Corp., Glenn Falls, N.Y., just received notice to proceed with a $765,000 emergency contract to build approach roads, parking lots and temporary facilities for a 40-car ferry service, says Vermont Agency of Transportation spokesman John Zicconi. The agency will soon award a contract for waterside work, including temporary bridges to the ferry dock. “‘As soon as possible’—that is the mantra we are working with,” he says.

Soils crews from both states this month also collected borings for use in the design of the permanent bridge replacement. “A temporary bridge is not ruled out, but if we can get a new bridge going soon, we may not need it,” says Zicconi. NYSDOT already had $50 million in its capital budget for a new bridge to be constructed over the next decade, “but we are looking at a couple of years now,” says Dennison. If the legislature will allow it, New York will consider design-build, he adds.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment