Nobody loved Interstate 64 where it cut through the heart of St. Louis. It was a transportation bottleneck, with outmoded interchanges and crumbling bridges. Built largely between the 1930s and 1960s as U.S. Highway 40, it was rechristened I-64 by federal fiat in 1988 despite its failure to comply with Interstate standards. But when the Missouri Dept. of Transportation proposed in 2000 to rebuild it, worriers came out of the woodwork. And when MoDOT announced in 2006 that it would completely demolish and rebuild 10 miles of the central artery, public opinion went ballistic.

“It was top of mind,” the talk of dinner and cocktail parties, says Linda Wilson, MoDOT spokeswoman. “Not the Cards, not the Rams, not the war, not the stock market,” the topic was, “‘They are going to close my highway!’” she says. Opposition to the project was “really out there in 2007 when we first announced we had a contract,” agrees Ronald Morris, deputy project director. One newspaper headline predicted “Carmageddon.”

MoDOT responded with a full-court-press campaign of public information. Paired with the smooth execution of MoDOT’s first-ever design-build project, on time and even under budget, the project now has people saying, “This was the only way to do this job,” says Wilson.

The $535-million New I-64 Project is demolishing and rebuilding 12 interchanges, 30 overpasses and 10 miles of deteriorated highway and completing an interchange with I-170 that, people joked, ended in a Target store’s parking lot. “Every interchange was a bottleneck,” says Wilson. MoDOT engineers say the highway was carrying just 75% of its capacity because of the outmoded design. One on-ramp had a 15-mph speed limit, another was short, an exit ramp had a hairpin turn and there were several tight cloverleaf interchanges.

“We were most concerned about bridge conditions,” says Wilson. Half or more of the bridges were rated three or four on the federal scale, in which a new bridge is rated nine and a bridge rated two must be taken out of service. The need for the project was clear; the controversy focused on how it would be done.

During the planning, Wilson drove downtown with MoDOT Director Pete Rahn, briefing him on the project. He asked how long she thought it would take to rebuild the road, and she answered six to 10 years. He said, “You can do it in three.”

It appears he was right. Rather than specify how the contractor should do the work, MoDOT set goals for the contract, essentially performance specifications, and invited proposals for whatever could be built for a fixed cost of $420 million. The goals were standards established by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, rather than MoDOT specs, with completion not later than October 2010.

Picking a Team

The agency awarded the design-build contract in November 2006 to Gateway Constructors Inc., a joint-venture team consisting of Granite Construction Co., Watsonville, Calif., and St. Louis-based Fred Weber Inc. and Millstone Bangert Inc., with subconsultant Parsons Corp., Pasadena, Calif., as lead designer.

Gateway proposed to shut down, demolish, rebuild and reopen I-64 west of the I-170 interchange in 2008, do the same to I-64 east of I-170 in 2009, then complete the project by July 31, 2010, three months earlier than MoDOT required. Under that plan, Gateway is replacing 10 miles of the 11.5 miles MoDOT had targeted for reconstruction. The only competing proposal would have replaced about eight miles of the targeted section, with limited traffic flow continuing throughout the period.

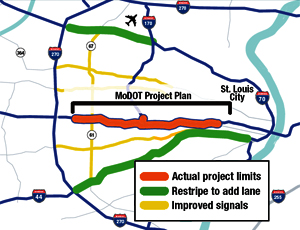

A key to making the plan work is the available network of Interstates and the region’s arterial roads. Traffic on the west half of I-64 is 170,000 vehicles per day; on the east half, 140,000. But MoDOT used 2007 to make its highways better, says Morris. Several roads were restriped to add a lane, and signal improvement already in progress on a major secondary roadway was speeded up to get the signal systems talking to each other and with the traffic-management center. Accident rates on the detour roads have not changed. “Everyone expected the rate to go up,” he adds.

Shutting down I-64 seemed an extreme approach, but a 2006 economic impact study by the state’s Dept. of Economic Development and Merrick & Co., Aurora, Colo., found that doing the project quickly and reopening the road would be better for the economy than keeping the road open for traffic and extending the project duration.

“The shutdown concept was the result of a collaborative effort that grew out of our many meetings with MoDOT during the nearly year-long period leading up to the proposal. In these meetings we went back-and-forth with our ideas, while MoDOT provided feedback as to what was most important to them,” says Don Rasmussen, project director in Granite’s Minneapolis estimating office. “The proposal process MoDOT used really facilitated ‘out-of-the-box’ ideas.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment