A solar tower planned to rise just 100 ft shy of the world's tallest building took a major step forward with the selection of Phoenix-based contractor Hensel Phelps Construction Co. as construction services provider under a guaranteed maximum price.

EnviroMission USA, a subsidiary of Australian renewable energy firm EnviroMission Ltd., is developing the estimated $750-million project, to be built on a site in La Paz County near Quartzite, Ariz. While the Australian division of design engineer Arup is still working out exact details, Chris Davey, EnviroMission USA's president, says the 426-ft-dia. tower is expected to reach approximately 2,600 ft into the Arizona sky. The great height is necessary to attain a sufficient temperature differential to propel air with enough force to drive the turbines.

While project financing is still being worked out, the project was boosted in October by a 200-MW power purchase agreement from the Southern California Public Power Authority.

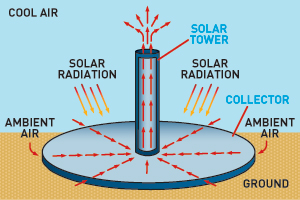

The tower generates electricity using relatively simple scientific principles. A massive greenhouse podium up to three miles in diameter will heat the surface air to 160 ˚F. Since air temperature falls 2 ˚F for every 320 ft in elevation, the difference in temperature atop the tower causes the lighter, heated air to flow upward. “Provided you can maintain the temperature differential of about 55 ˚F, you are going to operate at maximum output,” Davey says. Turbines similar to those used in hydroelectric powerplants convert the air flow into mechanical energy.

The solar tower's cost is high compared with other renewable power generating technologies, but Davey expects to identify significant savings to benefit future projects. The solar tower also has other significant advantages. “It doesn't use any water in the power production cycle, which is huge in the desert Southwest,” he says. “And most important for utilities, it's a non-intermittent renewable.” Unlike wind and traditional solar, which are reliant upon whether the wind is blowing or the sun is out, the solar tower works 24 hours a day, regardless of whether it is sunny or raining, since the earth acts as a giant heat sink to maintain the temperature differential even at night.

While the project uses materials that are readily available and components based on existing technologies, building one of the world's tallest structures in the remote and arid western Arizona desert will add significant complexity. “Because the site infrastructure is not developed currently to take the amount of traffic that is going to be required both from a materials and a manpower standpoint, the logistics [are] going to be a challenge,” says Steve Grauer, vice president and district manager with Hensel Phelps.

The initial design is expected to be delivered in the next six weeks and will likely specify reinforced concrete for the tower and a structural steel frame covered in a glass and ETFE plastic glazing system for the greenhouse. Arup previously used ETFE to clad the Beijing National Aquatics Center, which became famous at the 2008 Summer Olympics.

“Whether [the concrete] will be slipped or jumped, once you start to get over 1,000 ft tall, trying to work out the site logistics and get the materials to the work area becomes a challenge, as well as minimizing the time the crews are up on the deck at those heights,” Grauer says.

The project developer selected Arizona instead of the parent company's Australian base because of “the political and social will” in the U.S. and Arizona, “where people are looking for new forms of power generation,” Davey says. “This was more important than the incentives.”

With the project expected to employ up to 1,500 workers during its two-year construction phase, the project will receive job creation incentives from Arizona and federal solar power stipends.

Davey expects the tower to attain a 75-year life cycle, given its relatively low maintenance and operations requirements. Groundbreaking is expected to occur as early as the end of 2012.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment