Project managers are struggling with how to remove “Rainier,” a tunnel-boring machine that is stuck 330 ft underground since last year. Until the rig is moved, the area’s $1.8-billion Brightwater treatment plant can’t be finished.

“As of May 1, we have no way to remove it and are still working on a plan,” says Gunars Sreibers, project manager with King County, Wash. The tunnel, located 11 miles north of Seattle in Bothell, is designed to handle wastewater from King County’s northern reaches and part of neighboring Snohomish County. The majority of the project is expected to be complete in 2011.

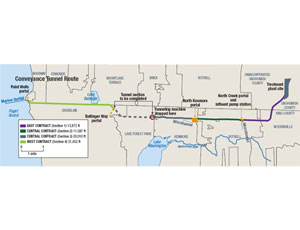

The 13-mile conveyance tunnel is being built under three contracts, using four 16-ft-dia TBMs. The two machines on the $211-million central-tunnel contract, managed by joint venture Vinci/Parsons/RCI/Frontier Kemper, became stuck in May 2009 when their cutter heads were damaged by glacial till. The Vinci machines were working from one portal, planning to drive 11,600 ft one way and 20,100 ft in the opposite direction.

The other TBMs—one operating under a west-tunnel contract managed by Jay Dee/Coluccio/Taisei (JCT) and another for an east tunnel under Kenny/Shea/Traylor—have not had any issues.

The central TBM moving east was repaired and back to work in February. It is “going gangbusters,” says Judy Cochran, King County tunnel conveyance manager. The TBM has completed about 1.5 miles of the 2.2-mile segment required. The other central TBM, moving west, is still seized up. Vinci submitted a $48-million change order to continue repairs, but the county refused to pay it. “The change order is still in negotiation,” says Annie Kolb-Nelson, King County spokeswoman for the Brightwater plant.

The dispute partly hinges on geotechnical information made available before drilling started. “Vinci claims it couldn’t anticipate the damage because it had insufficient information about large boulders and varying soil conditions,” says Cochran. “We think they mismanaged the slurry mix, which they’ve had trouble with since the project started.” The county claims it spent $10 million to test soils every 500 ft during the planning phase. The contractors declined to comment.

However, the county did pay Vinci on other claims totaling $6 million. “We still have about $26 million in our contingency fund,” Kolb-Nelson says. The owner isn’t waiting around for resolution, though. On Feb. 18, King County Executive Dow Constantine issued a declaration of emergency. This enabled the county to waive procurement requirements, cancel the boring work for the stuck machine and hire the west-tunnel contractor, JCT, to complete construction. Taisei has since dropped out of the emergency contract.

JCT is almost finished with its 4-mile portion of the tunnel job, which runs west to east from the outfall. When it reaches the end of its original contract, JCT will reconfigure and repair “Elizabeth,” a Lovat earth-pressure-balanced (EPB) unit, and continue drilling east to Kenmore.

How well is the Lovat machine suited to the next task? Engineers aren’t sure. The central segment is being built using two slurry machines manufactured by Germany’s Herrenknecht AG. Designers specified slurry machines because of poor soils as well as water pressure that is expected to reach 8 bar, or 116 lb per sq in. “Whether an EPB machine can do the job has been the subject of much discussion,” Cochran says. “Because of the high bar, the TBM will have to go through significant modification.”

Even so, the new contractor, already looking for a way out should it run into the same kind of trouble, has requested contract verbiage stating that it may not be able to complete the work. “We hope it can happen,” says Cochran. “The contractor wanted that phrasing so its reputation would not be damaged if it couldn’t finish the contract.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment