The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is banking on a fabric coating, better fill and changes in scour aprons and anchor tubes to make a 5.7-mile-long installation of berm with a sand-filled, geotextile-tube core the most resilient and long-lived geotube beach-hardening project it has built to date.

Weeks Marine Inc., Cranford, N.J., is 20% complete on a $25.7-million contract to restore the beach of Grand Isle, La., from damage caused last year by Hurricanes Gustav and Ike. The Corps is basing design changes on analysis of performance of an older, non-Corps installation in Galveston, Texas, in the same storms.

“We decided we needed to do something better because we’ve rebuilt Grand Isles a few times,” says Chris Gilmore, project manager with the Corps’ Hurricane Protection Office in New Orleans.

Weeks is moving dunes, trenching and laying down 30-ft-circumference, 200-ft-long sections of tubes. It is filling them with a slurry of sifted dune sand and water to create a hardened core. The top half of the tube fabric is manufactured with a 0.03-in. to 0.10-in.-thick polyurea coating material normally used to line concrete or steel tanks. It will protect the fabric from ultraviolet light and punctures and increase its life expectancy to 100 years.

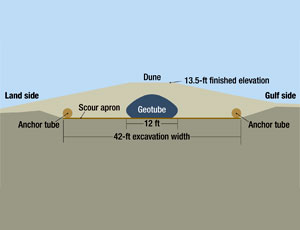

The tube is placed at +5 ft elevation on a 40-ft-wide fabric apron anchored by 7-ft-circumference tubes at both the gulf and landside edges. The main tube fills to an elevation of +10.5 ft. In August, Weeks will begin dredging an estimated 1 million cu yd of sand from an offshore site to cover the core and bring the finished elevation to +13.5 ft. The contractor will end by planting anchoring vegetation and building walkways for beach access.

The Corps expects the geotextile tube to protect residents and property and also maintain a fixed shoreline, even if storm surge washes away the covering dune. Since 1984, the Corps has spent $64.5 million building and repairing berms on the island on at least five occasions.

After Hurricane Ike, Grand Isle Mayor David Camardelle and Corps representatives went to Galveston to examine the performance of the tubes there. “We noticed significantly less damage behind the geotubes,” Gilmore says. Even though the state-installed tubes were made of “unprotected fabric with a life expectancy of 10 to 15 years and had no maintenance,” they protected against surge 15 ft to 20 ft higher than the tubes, says Robert Davinroy, senior project manager from the Corps’ St. Louis District, which helped HPO develop the plans and now is overseeing the Grand Isle work. “It’s not just the tubes but the system, which includes the scour aprons and anchor tubes and the dune on top,” Davinroy says.

In addition to the tough coating, improvements over the Galveston installation include broader scour aprons and larger anchor tubes. The apron on the wave side also is referred to as a curtain because when the surge is high enough to attack the base of the dune, the fabric falls down like a curtain. “In Galveston, it appeared the storm surge picked up the scour curtains, so we made them wider,” Davinroy says. The landside apron limits scouring at the back of the berm if overtopping waves cross the dune.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment