SPECIAL INVESTIGATION In the first few months of 2007, John Cherry worked on a survey crew for Shaw Coastal Inc. on the Amite River and other places in southern Louisiana. During some of that time, he would conduct surveys from a boat with another, more senior employee, Michael Reasoner, a project coordinator and safety manager who was needed to operate a hydrograph.

As the days went by, according to Cherry, Reasoner started to do unnerving things, such as brushing up against him and asking Cherry to remove his shirt or wear cutoffs. Despite Cherry telling Reasoner, a much shorter man, to back off, Reasoner over several days continued to make suggestions that implied he wanted to have sex with Cherry. Cherry says Reasoner also sent him salacious texts with messages such as "U R 2 Sexy " and explicit sexual references.

By September, Cherry was ready to quit. He complained to other supervisors at Shaw Coastal, a unit of Baton Rouge-based Shaw Group Inc., but the company's investigation found that it was only Cherry's word against Reasoner's. It seemed improbable, sexual harassment by one man against another—an idea that also has confounded judges in a handful of lawsuits brought by men during the past decade. While most similar same-sex harassment plaintiffs fail in court, Cherry sued in federal court and won a jury verdict of $500,000. After being thrown out by the trial judge, the verdict stood up in an appeal decided early this year. (Shaw is still appealing the amount of the award.)

Cherry's story of alleged harassment follows a line familiar to women who have worked in the building trades. But this and other stories of men harassing men in construction and engineering reinforces the idea that the harassment has less to do with sex than power and intimidation.

The depth of interpersonal pathology involved suggests how tricky it can be for employees to shield themselves from cruel or hot-tempered co-workers and bosses. Employers know they can't wave a magic wand that guarantees employees will refrain from illegal harassment based on gender, race or religion.

Bullying at work, when it doesn't involve race or gender, is legal. Yet a campaign by reformers has put workplace bullying laws in front of lawmakers in more than 20 states. If states start adopting such laws, the laws may afford protection to men who until now relied for relief on Title VII of the federal civil-rights law, which prohibits sexual harassment.

If that happens, the record on sexual harassment lawsuits suggests that employers can expect to win the majority of the time but spend heavily doing it.

Analysis Shows Most Claims Fail

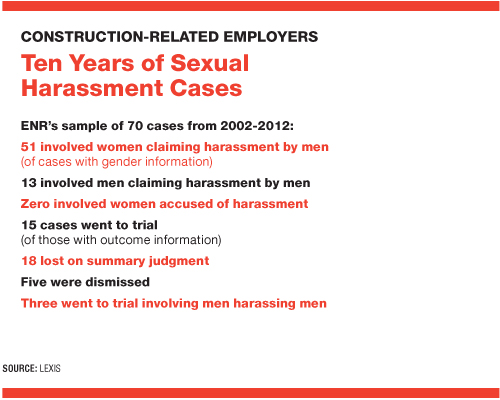

To illuminate the problems of harassment and bullying in construction, ENR collected and analyzed a sample of 70 sexual-harassment lawsuits brought against construction companies in the past 10 years. The research revealed many more failed claims than successful ones, suggesting that employers are doing a good job of successfully shielding themselves from liability. The employee faces a daunting task in meeting the standard needed for a case to succeed—that is, persistent harassment and a hostile environment that hampers the person's ability to do his or her job. The record also suggests that workplace anti-bullying laws introduced, but not passed, in about 20 states could provide a clearer refuge than current law for men victimized by bullying or sexual harassment—and unleash a wave of fresh lawsuits.

"This may sound strange," says Champe McCulloch, president of the Maryland chapter of the Associated General Contractors and a witness in 2011 against a proposed anti-workplace bullying bill introduced in his state. "Virtually every status other than 'white guy' is protected" by federal laws against harassment and discrimination based on race or gender. "If we wanted to disparage this, we could call [similar anti-workplace bullying prohibitions proposed in other states] the white-guy bullying bill."

Does that mean McCulloch believes bullying, whether it is expressed as sexual humiliation or not, is OK?

"No," says McCulloch. "We live in an imperfect world, and not everyone can be cured of imperfection" by laws and lawsuits. "Sometimes it takes good judgment and common sense. No law can deal with every situation with the nuance a company is required to use."

Legal scholars and social scientists say workplace bullying, which is prohibited by law in only two California counties and a few school districts across the U.S., cuts a destructive path across business, distracting and demoralizing employees who witness it and triggering depression and insomnia in its targets. In construction, ensuring that every employee is working without distractions can be the key to preventing accidents.

One contractor human-resources director says her firm has the issue firmly under control and that she is open to anti-workplace bullying laws because she feels her firm's employees already are held to a code of civil behavior. "Our training really covers bullying," says Patti Murphy of contractor Walsh Construction Co., Portland, Ore. "I would be supportive of anti-bullying laws because we have such a strong values system in place." She adds, more protections would not result in more lawsuits.

The biggest question is whether a legal definition of bullying would outlaw testy reprimands by bosses or make companies responsible for off-color exchanges between employees.

In examining court complaints and hundreds of pages of trial transcripts, ENR found that less than half of the cases in the sample were decided by a jury's verdict. In the case of male-on-male sexual-harassment lawsuits, the jury decision rate is only one in five. Judges make most of the decisions—usually in favor of the defendant—or the cases settle.

The small number of men bringing complaints and lawsuits regarding abuse in the form of sexual harassment may disguise the potential for many more abuse-related lawsuits. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics' most recent "Current Population Survey," construction industry employees are 90.8% male and 9.2% female. However, men in the construction industry file 19.2% of sexual-harassment and discrimination complaints with the U.S Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment