Many pavilion designers at Expo 2010 Shanghai, the World’s Fair currently under way in China, interpret its “Better City, Better Life” theme as a call for sustainable buildings. The Peru Pavilion is covered in “green” bamboo and clay, while the Japan Pavilion collects light, air and water in its “eco tubes.” But the developers of the Finland Pavilion interpret “sustainable” not only in terms of the materials and systems used in its construction, but also as an integrated process that begins in building information modeling and continues through adaptive reuse.

Contributors to the Finland Pavilion explained their thoughts on BIM integration on Aug. 18 as part of the “Better Building, Better World” seminar in Shanghai.

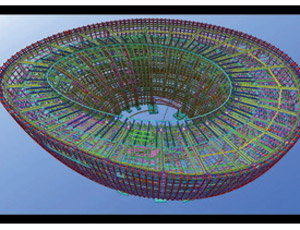

Finland’s 3,000-sq-meter pavilion, designed by Helsinki’s JKMM Architects, is named Kirnu, or “Giant’s Kettle,” and evokes the kettle-shaped cavities formed in Finland’s bedrock by glacial action during the Ice Age. Its hollow, rounded form is 60 meters in diameter and faced in a white material made from recycled pulp and paper. It sits in the center of a moat-like pond, emphasizing the glacial reference.

Engineers faced many challenges with the kettle’s asymmetrical double-curvature form, its use of bolted connections and the expo schedule, which gave them one year to move from design competition to groundbreaking and one more year to complete construction.

“From the day that Kirnu was chosen, it was quite clear that there is a need for 3D steel design software,” said Jouni Lehtonen, a representative of Finland’s exhibition organizer, Finpro.

Kirnu’s team created structural BIM models for both design and construction, using software from Tekla Corp., Espoo, Finland. The design team used the software to coordinate the architectural concept and production models as well as install planning and performance monitoring.

Stacy Scopano, director of global alliances at Tekla, described the “sustainability of data and methodologies” at the symposium, saying, “The key here is minimizing the possibilities of error in communication … error creating waste, error causing schedule delays. And that is one of the biggest opportunities that our industry has to tighten up its ship and operate more sustainably,” Scopano said.

Tekla’s software team collaborated on Kirnu with Trimble Navigation Ltd., Sunnyvale, Calif. Ken Shawler, Trimble’s Asia-Pacific sales manager, said the team improved the layout process “by simply putting the paper plans away. … Take an accurate model, bring it into a hand-held computer and connect that to a total station—by doing those simple things, you can increase your productivity, reduce schedule delays and increase your accuracy in the field.”

Trimble also provided as-built data for Kirnu. Says Shawler, “What a lot of people want is not a record of what the design was, but what was actually placed on the jobsite. We are able not only to set out points but also to collect data. We then provide a round-trip back into the Tekla software so they can lay those two bits of information on top of each other.”

BIM was key to the project, since the structure’s complex form disallowed repeating parts. Pekka Haanp��, design coordinator of Helsinki-based Lemcon China Co. Ltd., Finpro’s project manager, said, “With more simple calculation programs, the result would be that the engineer would say, ‘Let’s make a bigger pipe here and add more steel there.’ You make a more rigid building, but you waste lots of material—hundreds of thousands of kilograms in this kind of building.”

Haanp�� said that even if it were possible to draw the irregular kettle with 2D software, “when a change comes, for sure there will be a mistake. In the BIM model, when, say, you change a pipe size, it’s in the drawing automatically.”

In fact, purlins in Kirnu that had been specified as square-section elements were changed to round ones late in the design process, yet the building was completed for expo’s opening day of May 1.

After the Shanghai Expo closes on Oct. 31, the Finland Pavilion will be taken down. As part of its efforts to produce a sustainable building, the Finland team designed the building to be reused. The pavilion’s columns and connections were designed to allow for two office-height floors to be built within the existing shell, which means a buyer can choose to rebuild the pavilion as is or with one or two additional floors. Scopano says, “The software is poised and ready to take on these changes and automate them. … It gives the original owner the ability to provide variance … and increases the likelihood of resell.”

BIM has worked as a kind of translator on Kirnu. Scopano notes, “There’s a Finnish owner, architect and contractor, English-speaking consultants, and Chinese engineers and subcontractors. The 3D model defaulted to an international communication language in coordination and on the site.” Scopano says this technology also has been important in other work in China, where Tekla has had a presence since the late 1990s.

Tekla software has been used in other notable buildings in China, including Beijing’s “Bird’s Nest” and Shanghai’s Oriental Pearl Tower and World Financial Center. As Chinese builders vie to create high-performing structures and achieve LEED Platinum and China’s 3 Star green designations, it is likely to be used on many more.

Scopano says BIM is not just about making smaller numbers of people more productive. “There’s a quality component built into it,” he says. “As China begins focusing on the quality of the building products they have here, it begins to start demanding these kinds of innovations.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment