Six years after design began and one year after it was completed, Egypt’s Ministry of Culture is almost ready to start construction of the $550-million main building of the Grand Egyptian Museum, near Cairo.

Having secured a $390-million soft loan from Japan, the ministry last month appointed a team of Hill International Inc., Marlton, N.J., and EHAF Consulting Engineer, Cairo, to manage construction of the main building’s core, shell and fit out.

“We are hoping to get to the tender stage in the next 90-120 days,” and expect international contractors to bid, says Raouf S. Ghali, president of Hill’s Project Management Group (International). “The ministry is looking for the highest caliber,” he adds.

The project’s lengthy gestation is nothing compared to the antiquity of the ancient artifacts to be housed in the 500-hectare complex with 24-meter-high ceilings, partially buried in desert sand at the great pyramids of Giza. Already, the 12.5-m-tall statue of Rameses the Great, who ruled over 3,000 years ago, has been moved from Cairo for temporary storage near the museum site.

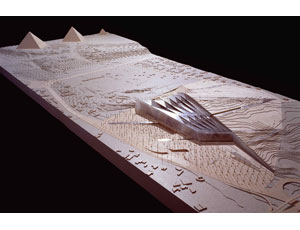

To prevent the sprawling complex from competing with the pyramids, two kilometer away, the 100,000-sq-m main building has been sited at the toe of an escarpment rising from the River Nile delta. “The pyramids are built at a higher level, but we decided we didn’t want our building at that level,” says Roisin Heneghan, a director of project designer Heneghan Peng Architects, Dublin.

In what was considered quite a coup for the small and relatively obscure firm, the architect beat some 1,500 international entrants in a 2003 design competition to win the design contract. All 20 finalists in the museum’s design competition hid the building from view; some had it totally buried, says Heneghan.

During the competition’s final stage, the architect recruited Arup Group Ltd., London, for engineering support, including structural, civil and facade design. Buro Happold Ltd., Bath, provided mechanical-electrical-plumbing engineering and information and communication systems. Both engineers worked with local partners.

Monumental concrete walls with immense hidden buttresses will be needed to retain the 35-m-tall escarpment. The retaining walls, hidden from view, will extend about 500 m, rising from footings more than 20 m deep. The walls will be heavily buttressed from the back at 6 m intervals.

“It’s going to be one of the largest retaining walls ever built,” says Francis Archer, Arup’s project manager. At least the excavation work will be easy, he adds: “It’s just sand.”

One of the largest visual elements in the design is a translucent stone wall, which includes 22,000 sq m of onyx, says Archer. Rising up to 40 m, the 800-m-long wall will stand 10 m from the front of the main building, to which it will be strutted for stability.

One of Archer’s concerns is the availability of enough onyx for the front wall. “We have to procure quarries,” he says.

The designers identified a couple of possible sources and advised the government to secure one with a “down payment.” But financial constraints appear to have prevented that from happening.

Thousands of triangular pieces of onyx, 40 mm thick, will form the imposing wall. The stones will be held in steel frames set on a triangular grid with sides up to 2 m long. The designers had strength and durability tests done over six months on a range of stone types at the U.K.’s BRE Group, Watford.

So far, local firms have completed the museum’s underground 18,000-sq-m conservation building and energy facility. A 220-m-long cut-and-cover tunnel will link the conservation and museum buildings. Already, millions of cubic meters of sand have been shifted, in advance of the main construction.

Main-building construction could last up to five years, say project sources. But the government is looking for a partial opening within 26 months of the start of construction, says Ghali.

The design team completed its work more than a year ago and has been waiting for procurement of construction contracts to begin, says Archer. Design was arranged in three distinct phases, separated by at least six months of down time, he adds.

While the design contract has ended, Heneghan hopes its team will be retained during construction. “We are talking to the client about an advisory role,” she says. “It’s a complex building,” she adds.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment