About 60 kilometers north of Fort McMurray, Alberta, the pavement ends. From Edmonton, the 440-km highway to Fort McMurray is a busy artery filled with construction workers shuttling to work in the oil-sands developments at the beginning of the week and home again at the weekend. Trucks crowd the road, carrying supplies to the burgeoning operational base. Wide and high loads are common for transporting oversized pieces of equipment or process vessels for installation.

The attraction is oil. Alberta contains one of the world's largest deposits of oil sands—an ore consisting of sand bound with clay and water coated with bitumen, a sticky, heavy hydrocarbon sometimes called tar with the flow characteristics of blackstrap molasses. Oil companies have been tapping the deposits for years but recent advances in mining and extraction have lowered production costs to a level competitive with global oil prices. That has sparked a building boom. The provincial utilities board has already permitted or is reviewing some 34 large projects worth an estimated $28.6 billion.

|

| TOPPED Recently completed coker is key part of Syncrude 21 expansion plan. (Photo courtesy of Syncrude Canada Ltd.) |

The Alberta Energy and Utilities Board estimates the province's oil reserves at 300 billion barrels, more than lies under Saudi Arabia. Now, scores of investors are pouring billions of dollars into schemes to mine the oil sands and extract and upgrade the bitumen to produce custom blends of synthetic crude oil. Other billions are going into the "in-situ" projects, where steam is pumped into deep deposits to melt the viscous bitumen, allowing it to be extracted through wells. All these developments require facilities to process the bitumen and refine the growing volume of synthetic crude, pipelines to transport the products, cogeneration plants for process steam and electricity and roads, bridges, power lines and gas pipelines to tie it all together.

On the $4.3-billion Horizon Project, one of the largest mining developments, roughly one-eighth of the investment will be spent on opening the mine, says an official of Canadian Natural Resources Ltd., Calgary. The rest—approximately $3.75 billion—will go for construction of facilities and infrastructure. Proportions on other projects may vary, but with more than $28 billion in investment projected over the next 10 years, the construction industry by any calculation stands to reap a bonanza of its own (see table).

The boom has been a long time coming. The resource's existence has been known since 1778, and attempts to develop it began about a century ago. But the pickings were easier and the quality of the crude was higher elsewhere. The hefty investment required all but priced Alberta's tar sand reserves out of the market. When Great Canadian Oil Sands, Ltd. the predecessor to Suncor Energy Inc., began commercial production in 1967, its cost was more than $23 per bbl. When Syncrude Canada Ltd., a joint venture, opened a larger open-pit mine nearby in 1978, its cost was similar. But by the late 1990s, according to the Calgary-based Petroleum Communication Foundation, costs had fallen to around $8.70 per bbl, competitive even with the $10-per-bbl low reached by world oil prices in 2000. Investors took notice.

|

| WELL PADS Mackay River development is one of new wave of SAGD projects. (Photo courtesy of Petro-Canada) |

Several factors finally came together in the mid-1990s to make oil-sands development attractive, says Gareth Crandall, vice president in the Calgary office of energy consulting firm Purvin & Gertz. One was the declining resource base of conventional oil in western Canada. "We've found all we're going to find," he says. In-situ development of heavy-oil deposits in the 1990s also played a role because 90% of the oil-sands resource is beyond the reach of surface mining, he adds. Syncrude and Suncor got their costs down to around $10 or $11 per bbl in this period. That cost could not compete domestically if light oil were available but it is globally competitive. Enhancing its attractiveness is the fact that "there's no political risk, and a huge resource base," he says. "People began to realize this oil [compared to natural crude] is not very different from a quality point of view."

Shell Canada, leading a consortium that includes ChevronTexaco and Western Oil Sands Ltd., was one of the first of the new investors. In 1997, the consortium announced its intention to develop the $3.3-billion Athabasca Oil Sands project. The program is opening the 155,000-bpd Muskeg River Mine 70 km north of Fort McMurray and adding an upgrader to Shell's Scotford refinery north of Edmonton. Shell is investing $283 million more in modifications to Scotford so it can process the new feedstocks from the upgrader.

Elsewhere, Corridor Pipeline Ltd., a wholly owned subsidiary of BC Gas Inc., just completed a 493-km, $370-million pipeline from Muskeg River to Scotford and on to the Edmonton area. ATCO Power, a subsidiary of Edmonton-based developer ATCO Ltd., is developing a $125-million, 172-Mw cogeneration plant at the mine and an $88-million, 150-Mw cogeneration plant at the Scotford refinery. ATCO Pipeline is building a $23-million, 118-km natural gas pipeline to supply the mine and its powerplant.

Click here to view: Largest Oil Sands Projects

On the heels of the Shell projects, CNRL announced the Horizon Project in 2001. Suncor already had embarked on its $1.3-billion Millennium Project, a 225,000-bpd surface mine with a new primary extraction plant, upgrader and other facilities. At the same time, Syncrude was going full-tilt on its $5.2-billion, 10-year Syncrude 21 expansion to double its synthetic crude production to 170 million bbl per year.

Responding to demand, Fort McMurray's population grew 16% in just one year, reaching more than 42,000 in 2000. But the simultaneous construction of several major projects has seriously strained the remote area's market for skilled labor. As a result, the Athabasca project's cost estimate has ballooned 36% from its original $2.4 billion, and the estimate for the Scotford upgrader has been revised upward from $251 million to $283 million.

|

| TOPPED Recently completed coker is key part of Syncrude 21 expansion plan. (Photo courtesy of Syncrude Canada Ltd.) |

"Labor availability has been a significant challenge, particularly over the past six months, and productivity has been well below the levels assumed in original estimates," Shell officials said when announcing the revised estimates in November 2001. They expected availability and productivity to improve with the completion of some other industry projects.

Labor is a worry, although most shortages to date have been short-term, says Richard Carter, executive director of industrial relations for Fluor Constructors International Inc., Greenville, S.C. Problems in garnering enough skilled workers reflect the overall industry-wide trend. "The labor is just not around," he notes, pointing to shortages in the number of welders, pipefitters and boilermakers in particular. Local unions are stepping up their apprentice programs to meet demand, he says.

Other projects also have experienced escalation. The cost of Suncor's just-completed Millennium Project shot up 70% from $1.3 billion to $2.1 billion in two years of construction. Says Purvin & Gertz's Crandall, "We just found out in the last two years how difficult it is to build several projects at the same time."

Chastened, the producers responded with a variety of measures to avoid repeating the experience. A dozen major companies and cities formed a regional infrastructure working group to coordinate construction planning, transportation, housing and other matters related to the expansion, says Réal Doucet, CNRL's vice president for oil sands, who represents CNRL to the group. The company also is coordinating phasing of construction of the Horizon Project with others in the area.

Suncor is responding with an overhaul of its approach to construction. The Millennium Project was built using an alliance, but "we were severely overextended. It was not a pleasant experience," says Derek Baker, operations vice president for the company's recently launched Firebag in-situ project. For Firebag's $280-million first phase, he says, Suncor is hiring two dozen people to perform conceptual engineering and procurement. Detailed engineering will be done by an outside firm. "We're going to be much more in control of the [engineering, procurement and construction] than we have been in the past," he insists.

Construction of in-situ plants allows for economies through repeatability because well pads are largely identical, says Baker. The Firebag project will be developed to produce 140,000 bpd in four stages of 35,000 bpd each. "We see ourselves building in-situ projects for 10 years to come." The new construction organization will give Suncor greater control over the design and cost of the projects now being planned.

But these megaprojects are only the tip of the iceberg. Billions of dollars more will be invested in a huge array of projects. The region's fourth major oil-sands development may be TrueNorth Energy's Fort Hills project. The partnership of Calgary-based TrueNorth and Toronto-based UTS Energy is preparing regulatory applications for a $1.3-billion surface mine. Plans call for 95,000 bpd of production by 2005, growing to 190,000 bpd by 2008.

|

| TWINNED Two-lane road was expanding to handle growing Fort McMurray traffic. (Photo courtesy of Petro-Canada) |

Husky Energy in January announced its intention to accelerate development of its oil-sands assets in Alberta. Delineation drilling is under way in the Athabasca region, and the company expects to begin front-end engineering design this year.

BC Gas in January announced that it will build a pipeline from the Fort McMurray area to transport bitumen to refineries in the Edmonton area. The 320-mile, $625-million pipeline could be onstream by 2005, the company says.

But oil and gas prices and similar economic factors ultimately will decide how many of the projects get built. Gary Pichach, senior vice president at Macdonald Engineering Group Ltd., Calgary, says he's noticed a slowing in the pace of several projects since Sept. 11. "Nothing's been canceled, nothing's delayed, but they have less aggressive schedules," he says.

Crandall worries about the potential impact of tightened regulation. "If the Kyoto Protocol is approved, it could have a negative effect," he says.

And labor availability and productivity will continue to put pressure on costs. Dave Thompson, project manager for mechanical subcontractor Horton CBI on Syncrude's $2-billion upgrader expansion, says craft people are skilled, but there's a lot of stress. "For a man to leave his home in Edmonton to go to a job that's five or six hours away and only get home on weekends, we have to pay top dollar."

It's important to stay aware of competing projects. To keep people from jumping ship for a refinery turnaround simply because it offers more hours, for example, Thompson adds hours and pushes to get things done quickly when labor is available. But "you build contingencies in the schedule in expectation of short labor," he says.

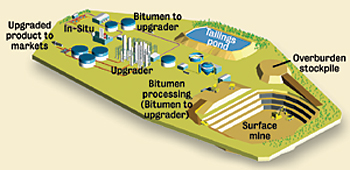

Two Ways to Process Oil SandsCNRL's Horizon Project offers a good overview of the kinds of construction required for oil-sands development, since it comprises both surface mining and in-situ development. At the surface mine, huge shovels strip out ore and load it into heavy-haul trucks. The ore is transported to sizers and breakers, where it is crushed, mixed with water and solvent, and fed into a hydrotransport pipeline. The extraction process begins here, where solvent and water begin to separate bitumen from sand and clay. The bitumen-processing plant completes the separation, sending bitumen froth to an upgrader. Tailings are shunted first to a holding pond and eventually returned to a mined-out pit.

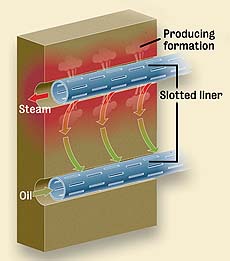

In-situ methods make more economic sense for deposits covered by more than 75 m of overburden. Two of the most common are cyclic steam stimulation (CSS), also known as "huff and puff," and steam assisted gravity drainage (SAGD). Imperial Oil Ltd. first found commercial success with CSS in 1985 at its Cold Lake site. SAGD is a newer technology. Alberta Energy Co. built the first commercial-scale SAGD plant at Foster Creek in the fall of 2001.

Both technologies require construction of well pads and extensive water-treatment facilities. "An in-situ project is mainly a water-treatment plant," says Derek Baker, operations vice president for Suncor's new Firebag in-situ development. The operation requires a steam generator, a plant to separate the heavy oil and water emulsion that is pumped to the surface and facilities to clean the water before it is recycled through the steam generator. A pipeline transports the heavy oil to the same upgrader that serves the surface mine, and another pipeline delivers the upgraded product to refineries farther south. In addition to the processing and support facilities, utility infrastructure must be expanded: roads, bridges and work force housing are required for remote locations. Most major oil-sands projects include an onsite cogeneration plant. |

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment