|

| FREQUENT FLYER Fredric Berger followed his father's path in building a global practice. (Photo by Micheal Goodman for ENR) |

Berger Group, the big design and development consultant known for working in poor nations, found itself in unusual company this spring when the Bush administration was picking reconstruction contractors to work in Iraq. In news stories identifying contenders for the contract, which Berger did not win, the company was referred to as one of the U.S.'s "Big Five." The other companies were Bechtel, Fluor, Halliburton and Washington Group.

That tickled Derish M. Wolff, the 68-year-old chairman of Berger Group, partly because he knew that with total revenue of $443 million a year, his company is much smaller than Bechtel or Fluor, and that its place on the list was owed to deep international experience, not size. During a news conference, the administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development, Andrew S. Natsios, pointed to Berger's use of local contractors while rebuilding a key highway in war-ravaged Afghanistan as an example of how the Iraqi jobs should be done.

But the publicity also signified that Berger's services in nation buildingconsulting to promote economic growth, self-sufficiency and stable institutionswas in demand and high on the Bush administration's agenda. Berger's portfolio is full of nation building assignments that, in recent years, have included converting former Muslim insurgents in the Philippines into business-minded farmers.

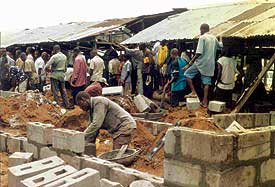

|

| ONE BRICK AT A TIME Community-chosen project in NIgeria, run by Berger, is designed to reduce poverty and social tension there. (Photo courtesy of the Berger Group) |

A critical part of Berger's strategy has been to cultivate contacts in the developing world, which requires the engineer to hold its own with heads of state and Harvard-educated government technocrats. The firm has worked regularly for international financial institutions and government aid agencies in places torn by war and civil strife, including the Balkans. But since Sept. 11, 2001, nation building has a new urgency. "I never dreamt it would be an attractive market in the post-Cold War period," says Wolff.

In fact, the East Orange, N.J.-based company has turned its work in dicey corners of the world into a stable, low-margin business, recording fewer write-offs than on its higher-margin domestic design and consulting. Berger has invested its profits in new domestic ventures. These include VMS Inc., a Richmond, Va., joint venture formed in 1995 that performs outsourced transportation operations and maintenance. Berger has also bought well-known design firms, including the 1994 acquisition of bridge designer Ammann & Whitney, New York City, which was in financial trouble, and last year's acquisition of a stadium and arena architect now known as Berger Devine Yaeger, Kansas City, Mo.

The story begins 50 years ago with Louis Berger, a Ph.D. soil and foundations engineer from Lawrence, Mass. When federal highway spending began to slow in 1959, he turned his domestic transportation design practice into one concentrated in overseas projects.

Berger copied the heavy customer service style of an engineering rival, New York City-based TAMS, to win in that same year the Rangoon-to-Mandalay road in present-day Myanmar.

The globe-trotting Berger, known to many as "Doc," spent much time on the road during much of the next two decades. But he also found time to cultivate two heirs apparent. One is nephew Wolff, a prolific storyteller who says he "has a theory on everything." The other is Berger's son, Fredric S. Berger, now 56, a passionate and worldly engineer whose bowties give him an academic air. They, too, took to the road developing close contacts in far-off lands, including South America. Most often, the firm put together studies that required a combination of economic forecasting and engineering feasibility, and that often led to design contracts.

With almost all its work coming from overseas, Berger called on staff with backgrounds in development, languages and overseas service, such as the Peace Corps. In the 1980s, as they became more experienced, Berger faced new corporate competitors and had to use more freelance consultants to hold down costs. This allowed the company to bill out for almost every hour and expense associated with its work, an enviable model but one that required close oversight by veterans.

|

| RISK? Wolff says foreign work is reliably profitable. (Photo by Micheal Goodman for ENR) |

The biggest challenge today, says Wolff, is making sure Berger doesn't put together a design team when a feasibility study still is needed, or vice versa. It also must make sure that its freelance consultants don't start applying theories that differ from Berger's core approach.

"They exploit top experts that float in the world market and get to know which to trust and which will work right, and it helps them in pricing," says Richard Fox, president of Cambridge, Mass.-based CDM. Berger also opened small offices in many places. "It used to amaze me that in every little corner of the world there was a Berger office," says Gerry Schwartz, a retired Jacobs Engineering executive and former president of the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Consulting services that Berger is willing to perform can go far beyond traditional engineering and feasibility studies. In Afghanistan earlier this year, the U.S. and Afghan governments hired Berger to collect existing paper money, incinerate it and replace it with new national currency.

Wolff emphasizes the work is not always risky and low profit. "We debate that with our auditors when it comes to reserves," he says. When the client is an international bank or U.S. aid agency, the payment risk is small. While a foreign government client may force the firm to wait as long as nine months for the first payment, the flow of money is usually as reliable as on a U.S.-funded job and can last for years, says Wolff. Overseas economic and feasibility studies only provide profit margins of a percentage or two, but those from domestic transportation departments, airports and environmental consulting are more than twice as high.

|

| HOT SPOT HERO Engineer Feibel helped turn Fillipino rebels into self-sufficient farmers. (Photo curtesy of the Berger Group) |

Berger makes good use of its money, turning its capital eight times a year, says Wolff. A profit of 2% gives it a 16% after-tax return on capital. Wolff and Berger together own slightly more than half of the company. (The next-biggest stockholder is François Farhi, who built up its African consulting practice.)

Fredric Berger treats the company's work as a cause, serves in many volunteer positions and is openly critical of some Bush administration and World Bank policies. He contends that a key bank problem is an in-bred culture that performs much research never made public.

Berger Group may be opinionated but its employees also know customer service. "What I like...was that it was one of four companies you could pick up a phone to and get thoughtful advice from," says J. Joseph Grandmaison, a director of the U.S. Export-Import Bank who worked with Berger while in charge of the U.S. Trade & Development Agency.

That customer focus won't change anytime soon, even as a new generation enters the firm's top ranks. Wolff last year gave up his chief executive title to Nicholas J. Masucci, who started the VMS venture and has concentrated mostly on domestic work. Chief Operating Officer Michel Jichlinski has much overseas experience.

|

| NEXT GENERATION Masucci is new Berger CEO. (Photo by Micheal Goodman for ENR) |

So-called pure engineers try to chide Berger for doing studies of rice paddies. But the firm's domestic acquisitions have added depth, and it is a partner on big domestic and international transportation design jobs. Berger also does significant aviation design, environmental consulting and program management.

But the firm's cultural fluency remains its core. One recent TV news commentator noted that "building democracy can be good for the bottom line." Berger is business savvy but prefers to portray its staff as idealistic hero-engineers.

And to some extent, they are. One current hero is Charles Feibel, who headed the Filipino project involving the Muslim fighters. He "brought all of his skills from the U.S as well as international sensitivity" to the task, says Masucci. While details about crops or rural infrastructure change with each job, says Feibel, U.S. policy and Berger's services are based on the same idea: "People fight for many reasons, but at the end of the day they must have incomes to support their families."

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment