...on the structural steel data and it takes an intermediate format. There is not one technology to make it work." he says. "Theres a way to model that works, and a way to model that goes nowhere."

If the LDT project was the trial horse, V6 was the race. "GMs facilities side had been watching the production sides development cycle speed up and realized that soon the buildings were going to be on the critical path for new car development too," says Mauck. GM decided to apply the lessons learned in the 1980s empowering production through what Olivier calls "math-data exchange." It tightens production by using smart 3-D modeling to pass design data along the supply chain so each participants contribution can be incorporated faster, better and cheaper. In the building industry many are referring to the adoption of similar techniques as building information modeling, or BIM.

Proof

GM officials call the success with BIM at V6 "a momentous achievement" in itself. The proof is on the jobsite, Olivier says.

|

|

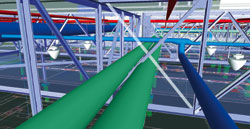

| Tight. Trimming on site is one thing, pre-fab to perfection is another. |

He recalls an exchange with HVAC contractor Dee Cramer, Holly, Mich. "Wheres your equipment?" he asked the contractor on the suspiciously sleepy worksite. "We pre-fab everything and bring it in and put it up," was the answer as Cramers on-site work force of eight popped long runs of ductwork into place. Building components to the 3-D model means no fabrication or trimming on-site, almost no dumpsters and little waste.

"If it fits in the model, it fits in the field,"says Mauck.

"It is different," admits Dave Babcock, Dee Cramer project manager. "When you go there its, where is everybody?"

"One of the business issues we push is lean construction," Olivier says. "We dont think the industry has embraced it. Well, 3-D design is a huge enabler for lean."

Getting the model completely correct, right from the beginning, is the key. Emdanat says that required some fundamental changes from everyone. But by last November, about the time LDT was getting over its growing pains, GM was ready to launch V6 and Ghafari knew what to do.

"On Nov. 7 we got the call...we co-located our teams and in three weeks placed the mill order and began fabricating steel," Mauck says. By the end of December the initial 3-D model was complete. Co-locating the teams by bringing designers and estimators from all disciplines into one big bullpen jump started the collaboration. Then, the real fun began.

GM declines to share the construction budget on the $300-million V6 plant expansion, but any GM-approved design savings or schedule efficiencies were shared among the team. "We had three weeks of value-engineering sessions with architectural, mechanical, electrical and structural," Ghafaris Neville says. "We developed $5.5 million in proposed savings, most in ductwork and mechanical, and electrical....We were throwing everything down that could be eliminated."

By then the design was 90% done. "We had enough data to put real things on the table," Neville says. At the same time the subs were pouring their designs into the model. On Fridays they would pass their work to Emdanat who would integrate it over the weekend and run the collision detection routines. On Monday they would meet as a team to view the results.

|

| Just Talk. Clash detection flagged issue when detailer flipped diagonal on last bay of truss. |

Initially, more than 3,000 collisions were found. For instance, fire lines ran through ducts, ducts ran through beams, trusses blocked piping in unexpected places. But in each case the issues were discussed, circled, and resolved. "When you catch them and there are no materials involved, its just talk, and well move it," Emdanat says. "All we did was circle it."

The subcontractors loved it. "When you get the 3-D review with everybody associated in the room, in eight hours you do what you probably would have done in a month," says Paul Sinelli, GM manager of capital projects. "The issues actually get resolved and people see progress."

One of the cast-in-stone business practices that was jettisoned was GMs rigid CAD standard, which would have interfered with the fluid integration of so much subcontractor specialty software. Another was GMs requirement for paper plan submissions for 30, 60 and 90% design review. It was simply incompatible with the live model review process, and after one influential in-house mechanical engineer sat in on the sessions and saw the light, that too was quietly let go. "We made some real believers out of some of those crusty old guys," says Sinelli.

Now, GM projects yearly savings on similar projects through interference avoidance of 3 to 5% per project, and thats aside from schedule savings, Sinelli says. "3-D brings it home. If it doesn't fit in the model, it wont fit in the field."

"I have never seen a project go through more efficiently," says Steve Hart, estimator for Dee Cramer. "Seeing everybodys conflicts and resolving them right there on the screen made it a lot easier. Our design in V6 went right over the coil line and cutting table and into the field. If we could only get every project like that. Its astronomically more efficient for everyone."

Adds Matthew Cramer, Dee Cramer president: "We had zero collisions with the other trades. The owner is getting a project delivered a heck of a lot quicker than they ever could have gotten, and its flat-out less expensive for them. Its an easier job to work on, and its win, win, win."

And the down-side? Hart has that pegged as well: "Theres not enough of them," he says.

(Images courtesy of General Motors)

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment